Banks are in a weird position right now. They need to make logging in both more secure and less annoying, which sounds simple until you start dealing with the actual technology and competing user expectations. Fraud attempts have gotten sophisticated enough that traditional passwords barely matter anymore – criminals have moved on to social engineering, credential stuffing, and SIM swapping that bypasses them entirely.

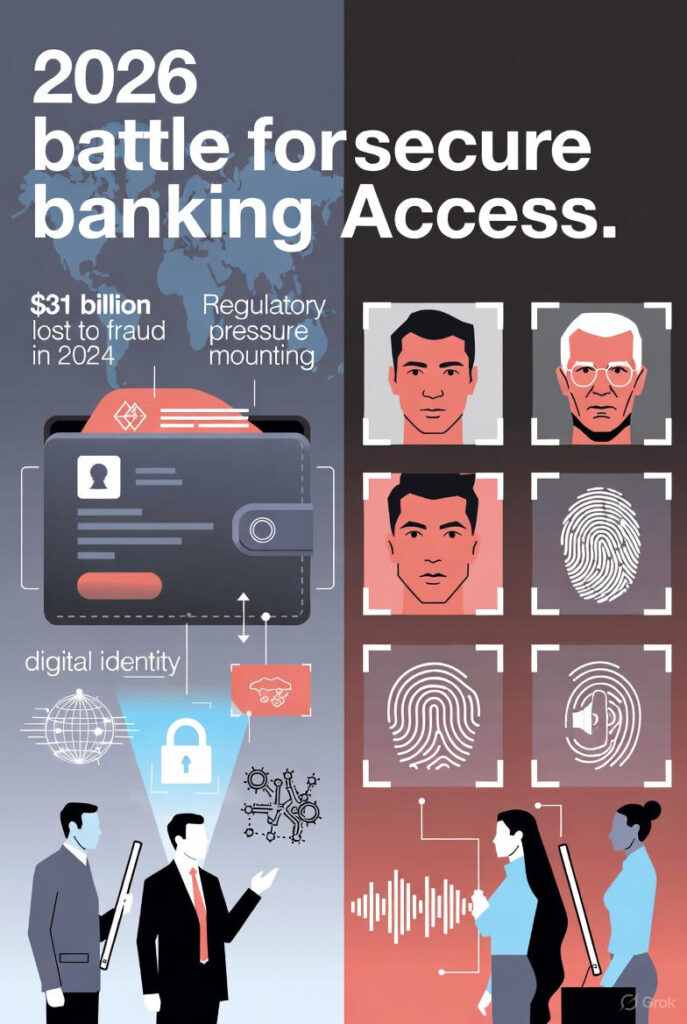

The statistics are genuinely alarming. Banking fraud losses exceeded $31 billion globally in 2024, and that number doesn’t capture the full picture because many incidents go unreported. Customers whose accounts get drained often blame the bank’s security, while banks point to user error like clicking phishing links or sharing verification codes. The truth usually sits somewhere in the middle, but the regulatory pressure on banks to prevent fraud has intensified dramatically.

Two approaches are competing for dominance in this security arms race. Digital identity wallets store verified credentials that you control and share selectively with your bank. Think of it like having a digital passport where you decide exactly which information gets revealed during each interaction. The bank verifies your identity without necessarily storing all your personal details on their servers, which reduces what hackers can steal if they breach the system.

The wallet concept builds on principles of decentralized identity and cryptographic verification. When you open an account or authorize a transaction, you’re essentially proving you possess certain verified credentials without actually handing them over. The technical implementation varies – some wallets use blockchain infrastructure, others rely on encrypted secure enclaves in your device, and still others use cryptographic proofs that validate information without exposing it.

European banks have moved faster on digital identity wallets, partly because GDPR regulations created stronger incentives around data minimization and user privacy. Several EU countries already have government-issued digital identity systems that integrate with banking apps. The US has been slower to adopt, fragmented by state-level identification systems and cultural resistance to centralized ID databases, but private-sector solutions are filling the gap.

Biometrics take a different route entirely. Your face, fingerprint, voice pattern, or even typing rhythm becomes your password. Major banks have already rolled out facial recognition and fingerprint scanning for mobile apps, and the convenience factor is genuinely hard to beat. You look at your phone and you’re in – no passwords to remember or reset, no security questions about your first pet’s middle name.

The technology behind biometric authentication has improved substantially. Early facial recognition could be fooled by photos or masks, but modern systems use depth sensing, infrared scanning, and liveness detection that make spoofing much harder. Fingerprint readers have gotten better at reading partial prints or working with slightly dirty fingers. Voice authentication can distinguish between live speakers and recordings.

But biometric data creates a unique problem that security experts lose sleep over. Once compromised, it’s compromised forever. You can change a password, cancel a credit card, get a new driver’s license number, even change your phone number. You can’t change your face or fingerprints. This permanent risk makes putting all authentication eggs in the biometric basket feel dangerous from a long-term security perspective.

The nightmare scenario goes something like this: a major breach exposes biometric templates from millions of banking customers. Now criminals have your facial mapping data or fingerprint patterns. Even if banks immediately stop using those biometric factors, you can’t just grow a new face. You’re stuck either accepting the compromised security or finding banks that don’t use biometrics, which might become increasingly difficult as the technology becomes standard.

Biometric template security has improved with techniques like storing only encrypted mathematical representations rather than actual images, but the fundamental problem remains. Some researchers are working on “cancelable biometrics” that could be updated if compromised, but those systems aren’t ready for mainstream deployment yet.

What’s probably happening by late 2026 is a layered security system that uses both approaches strategically. Quick balance checks might use facial recognition because the risk of someone briefly seeing your balance is relatively low. Larger transactions or account changes might require your digital identity wallet plus a secondary verification. Wire transfers over certain amounts could demand all three layers – biometric, wallet credential, and a time-based one-time password.

This risk-based authentication makes intuitive sense. Different actions carry different risk levels and should require proportional security. The challenge is implementing it without making the user experience so cumbersome that people start looking for workarounds or abandoning digital banking for less secure but more convenient options.

Banks are also experimenting with behavioral biometrics – analyzing how you hold your phone, how you type, how you swipe, your typical transaction patterns. These passive signals run in the background, building confidence about whether it’s really you accessing the account without requiring active authentication. If you suddenly start typing differently or accessing your account from an unusual location, the system might step up security requirements.

The friction point will be older customers and people without smartphones capable of running these systems. Banks can’t abandon those users, but they also can’t keep legacy systems running forever because maintaining parallel infrastructure is expensive and creates security vulnerabilities. Expect some messy transitions where different authentication methods coexist awkwardly until the technology matures and becomes more accessible.

There’s also a privacy versus security tension that hasn’t been fully resolved. Digital identity wallets offer better privacy by minimizing data sharing, but some banks argue this makes fraud detection harder because they have less information about their customers. Biometrics offer strong security but feel invasive to users concerned about how their physical data gets used. Finding the right balance will require both better technology and clearer regulations around data use and retention.

The regulatory landscape is still catching up. The US doesn’t have comprehensive federal legislation governing biometric data collection and use, leaving it to a patchwork of state laws. Illinois has the strictest biometric privacy law, requiring explicit consent and creating liability for breaches. Other states have weaker protections or none at all. Banks operating nationally have to navigate this inconsistent framework while trying to deploy unified security systems.

International customers using US banks face additional complications. A European customer might expect GDPR protections for their biometric data, while the same bank’s US customers have different privacy rights. Working out these jurisdictional questions in a digital banking environment where physical location matters less has created legal complexity that won’t resolve quickly.

Looking ahead, the winner of this “battle” probably won’t be winner-take-all. We’re more likely to see specialized use cases emerge where each technology fits best. Digital identity wallets might become standard for high-value transactions and new account openings. Biometrics might dominate everyday authentication where convenience matters most. And traditional factors like passwords and security questions will stick around as backup options when primary methods fail.

The banking customer experience in 2026 will likely involve switching between these authentication methods depending on what you’re trying to do, which device you’re using, and how much risk the bank’s systems detect in your specific situation. It won’t be seamless, but it should be more secure than what we had before – assuming the implementations don’t create new vulnerabilities in the process.